I was already awake before my iPhone alarm started chirping at 5:30 a.m. in the still starlit sky after sleeping maybe four hours due to a fully deflated sleeping pad in a tent on slightly uneven ground. Sometime after midnight, I had surrendered to simply sleeping on the cold, hard ground instead of the four inches of luxury I had the first night.

My new friend and trail mate rustled in his tent beside mine and asked groggily: “Is it morning already?”

“It sure is!”

Instead of waking up sluggish and resentful, I was eager—dare I say, even bright-eyed and bushy-tailed—to start the fourth day and last leg of my 40-mile trek on the Timberline Trail. Oddly, the only birds we heard were from my alarm as the real birds seemed to still be fast asleep in the evergreen forest surrounding us on this overlapping section of both Timberline Trail and Pacific Crest Trail (PCT) on the west side of Mount Hood.

We both swiftly dressed, broke down camp, and packed up our gear. Just as I was taking a bite of a Larabar and ready to hoist my backpack on, I looked up at my trail mate holding up his bear canister. “Breakfast?”

Sadly, I shook my head and full mouth.

As much as I wanted to linger, I couldn’t. I was on a mission.

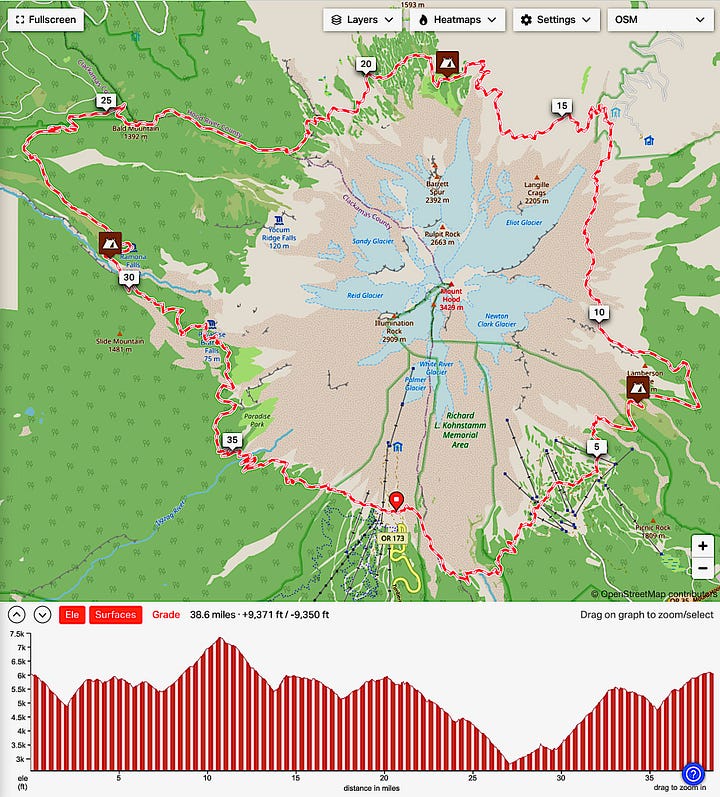

Not only did I have eight miles and 3,000 feet of elevation ahead of me before hopefully taking a celebratory lunch break in Timberline Lodge, but I also needed to drive the two-and-a-half hours back to Bend with a few minutes to spare for a shower at REI before my 6 p.m. closing shift. At the 1.5 mile/hour rate I’d averaged the past three days, I would be cutting it very close.

It reminded me of earlier in the summer on my magical visit to Crater Lake when I took a photo of two adorable newlyweds from Maine at the summit of Wizard Island before we became fast friends during the hike back, the boat ride, the hike up, and celebratory ice cream sandwiches at the visitor’s center. There was that joy of finding kindred company that’s as enjoyable as—if not better than—being on one’s own. As I sadly drove away from Crater Lake that day, I contemplated ditching my evening plans and camping another night to hang out with them longer, alas I knew it was time to go.

Just so, I put on my pack and set out on my own again.

After following the gray, ashy trail to the Sandy River, I watched the rising sun reflect off the mountain as I walked upstream until I found a log to cross around 6:30 a.m.—a nearly four hours earlier start than my first day. On the other side, I backtracked downstream until I saw an opening in the trees and headed back into the forest.

After a few minutes of hiking along a creek through the moist, temperate rainforest admiring the tall, mossy Douglas Firs the trail veered left at the first of countless switchbacks in my seemingly endless ascent for the day. Even with switchbacks crisscrossing uphill, there were sections with wooden logs built into the trail as stairs because the incline was so steep.

As my heart rate picked up, my mind fully woke up, and I laughed as I realized why this was the one section of the trail I couldn’t remember. I had literally blanked it out.

I tried to be here now by noticing the different types of ferns along the trail and naming the various sensations in my muscles—stiff, achy, tense, oh, and definitely tight—but my mind kept slipping away from the present.

I had flashbacks from the last time I did this endless slog uphill in August 2020, breathing heavily, with multiple blisters on each foot, crying from acute pain in my shoulder, and then once at the top refusing to take photos with my friends during our snack break in Paradise Park—the aptly named meadow full of wildflowers and boulders below the south face of the mountain that I couldn’t care less about—because I just wanted to be done.

Then, I recalculated my timing for the day, hour-by-hour, down to minutes per mile and drive time, in different configurations—beer and snack or beer and burger, shower or no shower, driving the speed limit or not—to figure out if I could make it back to Bend in time for work.

Around 7:45 a.m. almost to the minute when I had estimated my faster-paced trail mate might catch up with me, I heard footsteps on the soft soil behind me.

“Phew, this part’s a doozy!” I said with a head tilt, a smile, and a sigh of relief to have the delightful distraction of company again.

“I’ll say,” he replied.

And our conversation picked up where it left off. There was so much more to cover.

For instance, I learned more about his two-week farewell tour of Oregon along the PCT thru-hiking the Central Cascades Mountains, including Mount Hood, from the Columbia River Gorge back to Bend where he grew up, before relocating to North Carolina later that month. Even though he had already come and gone from Oregon many times, I understood how important it was to ritualize the transition.

“Dude, what’s up with the leaves?” he remarked, interrupting our conversation, as we came around a bend in the trail.

Everything was covered in fine brown dust.

A group of three hikers approached us from the other direction, so we asked if it was still like that further ahead. “What, you mean, the apocalypse?” they replied and we all laughed nervously.

When we came around a corner and emerged at what was usually a scenic viewpoint of the mountain all we could see was a thick white haze and winds blowing through the canyon at 30-40 miles per hour. Hence the dust covering everything. We were even more motivated to get back to the lodge and out of the smoke.

Over the next few miles through the forest, up and down the last river crossing and traversing scree, we discussed the air quality index, wildfire status, and various options for his trek from powering forward to calling it quits.

Before we knew it, we could see ski lifts ahead.

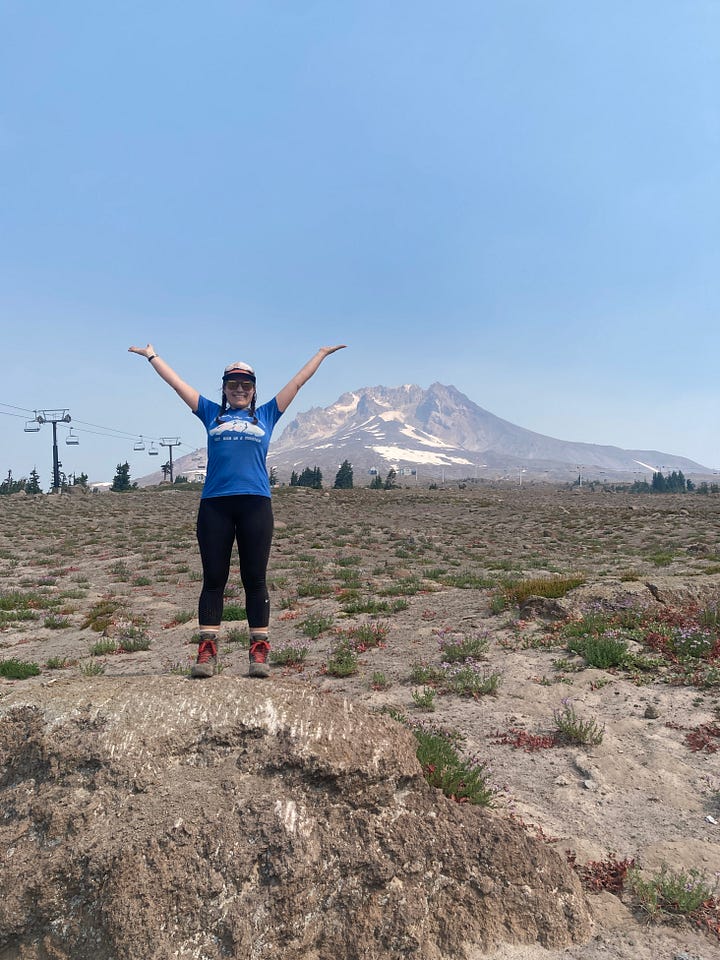

After a quick stop for a “summit photo”—my tradition in my Mom’s T-shirt from my parent’s climbing days in the 1970s—we hustled to the lodge for his resupply box and hopefully a quick lunch in the bar before I drove back to Bend and he decided how to proceed south along the PCT directly into the smoke and wildfires. Before going our separate ways later, I gave him my unused blister supplies and extra energy bars with a hug of encouragement and we set the intention to celebrate in Bend if he could indeed make it all the way there as planned.

When I turned my phone off Airplane Mode, the rapid ping of text messages immediately came through, including one from REI asking if I could come in early. At first, I laughed, but then I looked at the time and saw it was only noon. Hmmm, I actually had plenty of time to eat, drive, shower, and clock-in a couple of hours early.

In disbelief, I calculated that I’d covered the eight miles and 3,000 feet of elevation gain in around five hours. It was my fastest and steepest day yet. And I wasn’t even exhausted or complaining.

Talk about a comeback.

See highlights from Day Four of the Timberline Trail on Instagram.

See the whole Timberline Trail 2024 album on Google Photos.

There were so many stars that needed to align for me to get on—and stay on—the Timberline Trail, but I knew that was where I was meant to be. Somehow, all the stars did align—including the weather except for some smoke—as I hiked from Tuesday, Sept. 3 through Friday, Sept. 6, 2024, for my third time around the mountain and my first time solo.

Three nights, four days in the woods by myself. Sort of.

I met 18 people, one trail angel, and one trail friend; saw one marmot, dozens of chipmunks, and hundreds of birds; admired a million or so Lupines, Indian Paintbrushes, and Truffelumps a.k.a. Western Pasque Flowers; slept five hours per night on average; hiked approximately 9,500 feet of elevation into and out of 11 glacial valleys in three different ecosystems; crossed five major rivers, plus 25+ minor creek, stream, and brook crossings, and traveled about 9-, 11.5-, 11.5-, and 8-miles per day respectively, through 500,000 years of geologic time.

Up and down, all the way around.

As I drove down from the mountain—through the forest and mesas of the Warm Springs Reservation before the open land became farms and towns—I was already reliving the journey from my perfect first day to my fastest last day.

The mountain has four distinct sides, just like the traditional indigenous medicine wheel echoing the four directions, four seasons, and sacred path of both the sun and human beings as described by the National Park Services.

Each side feels like its own world, yet they make up a whole.

In many indigenous traditions, the four sides of the medicine wheel also represent the four aspects of self: the South is emotional, the East is spiritual, the North is physical, and the West is mental. I felt deeply connected to these as I navigated each side of the mountain.

For instance:

The emotions on that first day as I set out on my own from the south side, decided to continue solo when my friend and her dog bailed earlier that morning, relived memories of doubts and anxieties from past treks, and basked in the divine glory of alpine meadows on a bluebird day;

A spiritual connection between my intuition and my surroundings on that second day as I stayed attuned to the smoke, navigated the barren landscape without getting lost, visited the spot where we spread my Mom’s ashes, and met a trail angel in Elk Meadows with extra battery power to spare as I traveled up the east side;

That physically rigorous third day on the north side when I backtracked an extra mile to retrieve my trekking poles, hoisted myself one-handed up a rope to ascend the sandy Eliot Creek moraine, and took the steep downhill PCT detour to Ramona Falls;

And finally, the mental challenges of the west side on that last day to stay focused and mindful during the long slog uphill in order to finish strong, happy, and surprisingly ahead of schedule back at Timberline Lodge on the south side.

I learned so much more about these aspects of myself.

And, even though it was a solo trip, I also learned so many lessons about interdependence—receiving and offering mutual aid and support—from the other hikers, trail angels, and trail mates who I met, from my Dad remotely, from my Mom’s spirit, and even from the memories of my previous Timberline Trail trips with my friends.

The trail reconnected me to that deep knowing of how our experience of life is based on our circumstances and choices, our reality and attitude. It is cumulative. And it is cyclical.

Not only those four idyllic days on the Timberline Trail, but the last six months of recovering my broken leg, and the past four years that brought me back to the trail since my last completion in August 2020.

It was all a comeback.

Because we are always coming back as we cycle forward.

May you believe in the wild, pulsing life all around you this week.

Love,

Jules

Read the rest of the story: The Comeback: Part 1 | The Comeback: Part 2

this was beautiful, Jules! Thank you for sharing <3

I love the awareness of being solo and interdependent.

I also appreciate the cyclical knowing that shifts at each cycle.