On my second day of the 40-mile Timberline Trail, I woke up in my single tent near the noisy Newton Creek—about a quarter of the way around Mount Hood—feeling groggy and confused by the tampons falling out of my ears. Oh right. I recalled forgetting to pack my noise-canceling earplugs and the first few hours of tossing and turning after the sun went down before creativity kicked in.

My makeshift earplugs did not work, but the Benadryl must have.

Then, as I unzipped my tent and stepped outside, I smelled a whiff of smoke. It wasn’t from a neighboring campsite heating water for their coffee and breakfast; it was the unmistakable smell of a forest burning, somewhere.

This was not in the glorious weather forecast of clear blue skies that I said yes to on Sunday night. But, it was Wednesday now and a lot can happen in 48 hours.

After I methodically packed up my camp, including my inhaler and KN-95 mask in my first aid kit, I hit the trail around 8:15 a.m.—nearly two hours earlier than the day before. I hiked down to the river where there was excellent cell reception the night before. So good I accidentally texted too many friends and drained my phone battery down to 10 percent.

My iPhone battery had charged to 70 percent overnight, but the portable charger was half gone already, which meant I did not have enough juice to last three more days on the trail as anticipated and would need to be more careful with texting and taking photos.

As soon as I turned my iPhone off Airplane Mode, messages started popping up from my Dad as I’d hoped, including screenshots with heatmaps, showing red Air Quality Index (AQI) in the Central Cascade mountain range a couple of hours south but mostly yellow AQI near me. The wind pattern seemed to be heading east and I was heading north.

Exactly the kind of critical off-mountain support that my Dad always came through with based on his weather monitoring skills and decades of experience in the backcountry. If it was serious, I knew he’d tell me to get off the mountain.

It wasn’t ideal, but it wasn’t bad.

After an easy log crossing over Newton Creek, then a steep, seemingly endless climb toward the east side of the mountain, by mid-morning I emerged from the forest into a new ecosystem: the barren, wind-blown moonscape of Gnarl Ridge.

The trees grow sideways here, trunks hovering above the ground like roots, twisted and contorted like giant Bonsai, but somehow still growing. The white and wind-blasted skeletons of dead trees give shelter to new growth. High winds, no shade and little water, yet life adapts and persists.

I spotted a marmot scampering across the rocky cliff edge so decided to stop for a snack and a selfie while looking out over where I’d come from in the south. Up at nearly 7,000-feet of elevation, half of the state of Oregon is visible but I couldn’t see far because of a grey smog bank hovering over the horizon just like we’d had where I live in Bend, Ore. since mid-July.

Growing up here in Oregon since the 1980s, wildfires were smaller and less frequent. The mid-July to mid-October West Coast wildfire season now feels like an annual expectation instead of an accident, like the devastating Eagle Creek Fire in Sept. 2017, or an exception, like the massive Santiam Fire in Aug. 2020.

Just before Lamerson Butte, the highest point on the trail, I literally crossed paths with my first fellow backpacker of the day hiking the more typical clockwise loop. We stopped briefly to discuss the smoke situation that she was heading directly into before wishing each other good luck and happy trails!

Knowing the trail through this whole east side of the mountain had little shade or water, I kept up my pace toward my goal of a hot lunch by Cloud Cap Inn. I knew where I had to slow down to photograph the luscious bouquets of purple lupine in the alpine meadows or to consult the map so I didn’t lose time crossing the rock debris fields—the first of two places I’d been lost before—or to inspect the options for crossing snowfields—noticeably smaller than previous years.

I skipped visiting the Cooper Spur stone shelter and continued onward down the gray, ashy trail marked by giant rockpiles and wood posts toward the Cloud Cap Inn, a one-story, crescent-shaped wood building from 1889 now privately used by the Crag Rats mountain rescue group and only accessible certain months of the year via a 10-mile gravel road.

At the Cloud Cap campground, I took my time. This was one of the special spots on the trail where I wanted to linger, not only because of the amenities like a pit toilet and water spigot but its personal significance.

I switched from my hiking boots, socks, and liner socks to my flip-flops to let my sweaty feet dry out while I heated water for a spicy mango rice dehydrated lunch. I left my gear drying in the mid-day sun as I walked up the gravel road toward the inn, then cut back along the trail toward the spectacular view of the mountain that most people don’t know about.

This was where my parents came when they were in their 20s to sit and watch the sunset before their alpine start to summit the mountain by sunrise. This was where we spread my Mom’s ashes in 2018—the fifteenth anniversary of her sudden and unexpected death—into the wind and in a small pile below a beautiful, broken evergreen tree.

In my 2020 Timberline Trail trek, we camped at Cloud Cap and I watched the sunset from that same perch. Shockingly, the white, clumpy ashes were still there tucked beneath some small stones two years later. This year, I was relieved to see brown soil and only a few specks of white under the tree.

As long as I could briefly linger, I sat quietly on the nearby boulders eating my spicy mango rice and looking at the contours of the receding glaciers on the 500,000-year-old dormant volcano, yet vibrantly alive mountain.

See highlights from Day Two & Three of the Timberline Trail on Instagram.

Back at the campground, I noticed the only other hikers heading in the same counterclockwise direction as me from the previous day. I did not want to get behind their group of five for the afternoon, so I hustled to repack and redress and turned the first switchback down to the Eliot Glacier crossing just a minute before them.

I double-timed down the steep trail, crossed a makeshift log and rope bridge, located the trail connection a short way upstream, grabbed the rope with one hand while still holding both trekking poles in my other hand, and started pulling myself up the sandy incline.

Halfway up, in between huffs and puffs, I laughed out loud as it hit me: What is this rope connected to? Who put it here? Why am I still holding my poles? What am I doing?

But, I was in too deep to change course, so I kept hoisting myself and my 30-pound pack up single-handedly, then charged up the switchbacks on the other side until I was near the top and had enough distance from the group to finally stop, catch my breath and slow down my heart rate.

I still had a few hours of trail before my desired campsite at Elk Cove, so I re-paced myself, pausing for more photos of wildflowers in the burnout and alpine streams with long exposure, of course; asking passing hikers for beta, thus learning about bushwhacking through the Coe Creek crossing; and letting my mind wander to entertain itself, for instance doing a mental inventory of my closet about what to wear to an upcoming wedding.

Within a few minutes of arriving at the Elk Cove meadows around 5 p.m. pooped but thrilled to reach the trail’s halfway point on the north side of the mountain, another solo woman emerged from a clump of trees beside the trail and said hi like a trail angel dropped from heaven.

Like every other passing conversation that day, she was curious about what, if anything, I knew about the smoke, so I shared the morning’s AQI and wind pattern images from my Dad and what I knew about the trail ahead. Like almost everybody else, she too was heading in the opposite direction as me.

I had a hunch to ask her about any spare charging battery juice and before I knew it I was setting up my tent in the grove of trees beside hers while my phone charged. We made small talk while I unpacked and she cooked her dinner. I learned she was a wilderness guide from Wisconsin. And I discovered that my trowel was still at the previous night’s campsite. Dang it!

She kindly lent me her trowel so I could pre-dig a hole for the next day’s morning moment, then we walked over to the creek to filter water before quietly watching the alpenglow of fading light reflected off the mountain. After the sunset, we retreated to our tents; then woke and packed up well before the sun rose.

We said a quiet and quick, “Good luck and happy trails!”

And, just like that I was on my own again.

It had been a windy night with branches scraping the sides of my tent while I tossed and turned on my borrowed sleeping pad—which deflated twice, plus Benadryl did not work this time—so even though I was in my sleeping bag for nearly 10 hours, I maybe slept for five hours.

But, I still hit the trail around 7:00 a.m.—another hour earlier than the day before—to stay ahead of the forecasted heat and the unforecasted smoke. Twenty minutes later, after ascending above the meadows and looking back to snap smoggy photos of the rising sun, I realized my hands were unusually empty. Oh nooooo!!!

In my mind, I could see my trekking poles leaning against a scraggly trunk inside that little clump of trees down in the meadow.

There was no question what to do. I dropped my pack on the side of the trail, shoved my phone in my leggings pocket, grabbed my Nalgene of water, and started run/walking to retrace my steps down the three-quarters of a mile and 500 feet of elevation, across the creek, through the meadow, back to my campsite and then ran/walked back up.

I definitely earned a Snickers bar for breakfast, I reasoned.

After I hoisted my pack back on and set out with a pole in each hand only a half-hour behind, I marveled at how my body felt. Even with the sleep deprivation, all the elevation gain and loss on uneven terrain while carrying a heavy pack and lack of previous backpacking this summer as my broken leg healed, my legs felt stronger than ever.

This wasn’t an accident.

Little by little, rep by rep, my Physical Therapist and I had been working toward this for six months.

And, each familiar trail junction I passed reminded me of all the countless backpacking trips and conditioning hikes I had done, including right here on Mount Hood, throughout the past 10 years. Sure this was only my second backpacking trip of this season, but it felt like my body held a deep muscle memory of every one of those past miles.

And just like my first attempt, and subsequent summit, of this mountain, I was filled with that sensation of being highly capable and in my element.

It wasn’t easy, but it felt so right.

I swiftly traveled through more burnout of past wildfires, more creek crossings, another stone shelter in Cairn Basin, the tricky trail junctions near the ponds—the second of two places I’d been lost before, past all the deliciously distracting huckleberry bushes, far down the ridgeline seemingly off the mountain, then took a short cut-off as highly recommended by a group of Moms from the Tri-Cities heading in the opposite direction.

They were right about the epic view of the west side of the mountain—even with a bank of smoke hovering at the timberline. Just my luck, there were three tourists from Chicago on a day hike at that very spot, who happily took my photo, before I continued to the Top Spur junction where I could take my boots off, stretch, and eat a hot lunch.

See the whole Timberline Trail 2024 album on Google Photos.

As strong as I felt, I had no interest in crawling over and under tree blowdown from recent storms along the next section of the Timberline Trail, especially in the mid-afternoon heat, and opted to follow a detour down the steep switchbacks of the Pacific Crest Trail (PCT) to the creek that flows from Ramona Falls where I planned to camp for the night, then hop back onto the Timberline Trail for my final push back to the lodge the next day.

As soon as I felt the cool air wafting up from the flowing creek, my muscles ached to get in. I methodically undressed, hanging each of my sweaty layers on a tree beside the water, then gingerly stepped into the ice-cold water instantly turning my skin pink. After snapping a selfie, I sat for as long as my body could take it before redressing and reluctantly putting my boots back on for the last mile or so of the day.

Just a few steps back on the trail, I stopped to take pictures of the massive, undulating rock walls tucked behind the trees, when I heard a voice comment about how cool it would be to climb them.

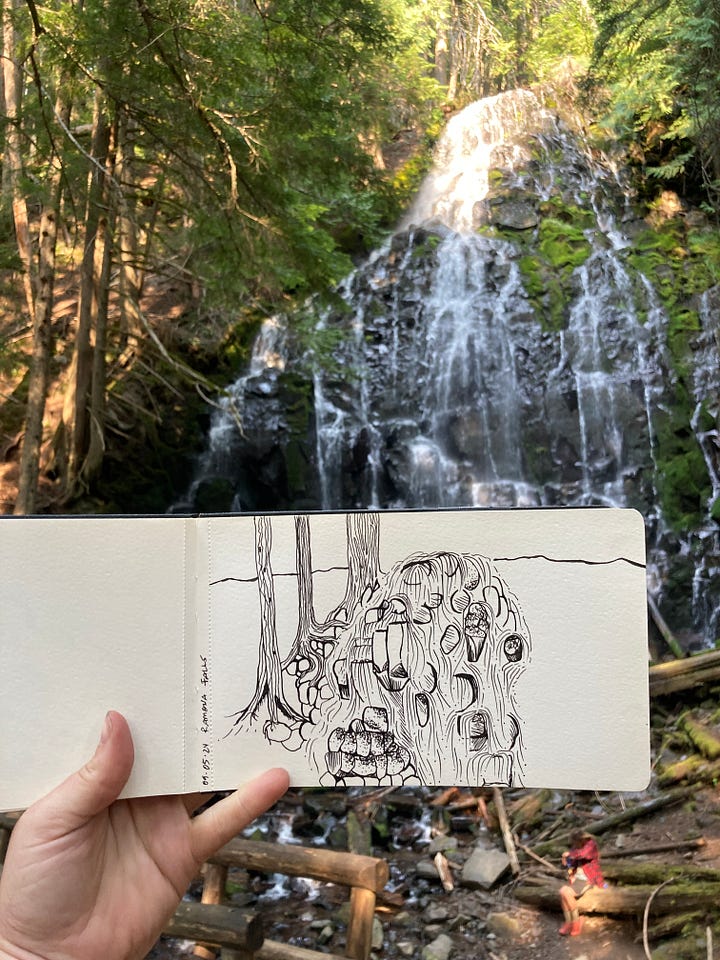

Surprised, I looked around and noticed another hiker had stopped a few feet from me with the same awe in his eyes. After some quick small talk about rock climbing, we continued chatting on the trail toward Ramona Falls where we both wanted to relax and take in the beauty.

One interesting comment led to another topic as I double-timed my pace to keep up with the conversation and his long gait. While I’d stopped umpteen times to chat with fellow hikers who crossed my path, this was the first time in three days that I’d actually hiked with someone.

This is how fast one makes friends in the wild.

After we’d snacked and stretched and filtered water and taken photos and I sketched while he read, we headed down the trail a bit in search of a campsite. He knew of a big, quiet spot off the PCT, which I immediately recognized as a spot where I camped years ago on a solo overnight, so after we unpacked gear, set up our tents and ate dinner, I showed him the little trail up the hill to an abandoned log cabin ranger’s station in a meadow.

Once the sun sunk from the sky after dinner, our conversation continued through the mesh of our respective tents as we girl-talked about our hopes and dreams and fears late into the night like college roommates.

Once the hush set in, I starred up into the starry night—without ear plugs, without Benadryl, feeling my borrowed sleeping pad starting to deflate, knowing I was unlikely to sleep much—and counted my lucky stars.

That the smoke was behind me and my Dad had my back. That I could feel my Mom within me with every strong, decisive step. That I hadn’t lost any more gear and again had a trowel to borrow for my morning moment. That I had plenty of food to share with good company and great conversation. That I knew this mountain like a lifelong best friend.

That when everything was stripped away, my every need was still being met—by myself, by others, and by the wild pulsing life all around me.

May you believe in others this week.

Love,

Jules

Read the rest of the story: The Comeback: Part 1 | The Comeback: Part 3